Social Network for Knowledge Workers

When it comes to understanding or discussing social products, I align myself with the Social Capital theory camp. This theory is heavily discussed by Julian Lehr and Eugene Wei. To further understand this concept, Tim Urban's metaphorical representation of how the human mind works can be helpful, as outlined in his article Religion for the Nonreligious.

There are three basic yet fundamental principles of human nature:

- People are status-seeking monkeys

- Many of our everyday actions can be traced back to some form of status-seeking

- Our brains deliberately hide this status-seeking fact from both ourselves and others (self-deception)

When we do something, there's usually a hidden message we want to convey to signal our status. This is called signaling, which has three components:

- Signaling message: the hidden subtext you are trying to convey

- Signaling distribution: the way you get a signaling message across to other people

- Signaling amplification: the amplifiers you employ to help you better compete against status rivals

Social networks are naturally effective at signaling distribution. They typically use different proof-of-work mechanisms to allow users to prove their signaling messages. For example, on Facebook, an interesting post with a combination of text, images, or external links can serve as proof-of-work. On Instagram, a creative image (originally square) and/or a short video can serve as proof-of-work. Additionally, metadata such as location can help boost the credibility of a message. Tools such as Instagram's image filters can also amplify signaling by making a message look more appealing.

The power of these networks lies in their ability to enable users to accumulate quantifiable social capital, such as followers, views, likes, comments, etc., by performing the proof-of-work tasks they have been designed for.

Good and bad of social networks

When it comes to knowledge workers (my discussion will be limited to them), let's be honest - we often compete to appear smart. For example, on Twitter, people post tweets expressing various opinions on different topics. For what? To demonstrate their expertise on the subject.

On one hand, this is beneficial because it allows us to access information we wouldn't have otherwise. However, it can also lead to information overload.

It turns out that they are just poor enablers for discussion and learning, especially for people who want to dive deep into a topic. We have seen people revert back to active learning by manually seeking out information from different sources and having direct discussions with others.

Social networks are useful for discovering information, but they are not helpful for knowledge workers looking to improve their knowledge.

Market entry

Disruption Theory is a useful framework for understanding market entry. Within the theory, there is the concept of who the overserved customer is: the customer whose needs are exceeded by existing solutions.

Driven by competition and the motive of monetization, mature markets often provide overservice to their customers. Consider the softwares and services we use on a daily basis. How many of their features are actually used? Overservice results in customers having to pay more or experiencing a poor user experience.

In our case, social networks need to increase their network size to defend against new entrants (network effect = moat) and improve monetization. However, this can lead to a poor experience for end users, who may struggle with creating and consuming content.

When targeting overserved customer, new entrants typically lower prices and/or improve their user experience (exact feature sets and UX improvement of certain features). For software products, usually it’s the later. This is the case with the Contact Finder feature innovation you implemented.

However, this is very difficult to pull off. There is a formula for calculating a product’s perceived value by new customers: perceived value of a new product = ( new experience - old experience ) - migration cost. For social products, the migration cost is simply too high due to network effect making the perceived value of the new product negative (likely).

In your previous email, you mentioned underserved communities. We need to be cautious when targeting underserved customers. It's important to understand why they are underserved and why no good solutions currently exist. Is it due to technology limitations, legal or regulatory issues, or is it simply too small of a market?

As an example, let's look at the Hyperhidrosis group you mentioned. They are underserved precisely because there are no effective or safe medical treatments available. This is not a matter of finding better information, but rather a research issue in the medical field.

The best market entry strategy is to identify customers who are both overserved and underserved by existing solutions. Customer needs tend to be hierarchical, with a product or service often overserving one need but underserving a higher-level need. Here are some examples:

- Before the iPhone, we were overserved with feature phones for communication (just look at the abundance of installed garbage apps and poor UX), but underserved with internet services on the go (just look at the WAP sites we used to use on Nokia phones). Then the iPhone came. It was not just a better phone, but an internet-on-the-go phone.

- Before WeChat and WhatsApp, we were overcharged by mobile carriers for sending SMS messages (having to pay per message or purchase a package with a message count cap), but underserved when it came to staying connected with our loved ones.

- For Uber, owning a car is unnecessary for going from point A to point B at a certain time. Uber provides a superior alternative.

- Let's consider note-taking for knowledge workers, which is relevant to our discussion. Many note-taking apps from previous generations, such as Evernote, Bear, and Ulysses, focus too much on the presentation of notes, offering features like full markdown support or MS Word-like WYSIWYG editors, but they lack a basic understanding of knowledge workers' needs, which is to become better thinkers or more knowledgeable in certain areas. Roam Research, Obsidian, Notion, or similar apps are better suited to serve this higher-order need

Effective learning usually involves the following steps: discovering good information → digesting (note taking) → reviewing → shaping up your understanding.

Social networks are a useful resource for discovering information. However, due to their business model, they often lead to overuse. In other steps of effective learning, they simply do a poor job.

A social network for building your knowledge graph

What job-to-be-done can we improve for knowledge workers?

What is the leading indicator or metric for a knowledge worker to understand how much they have improved or to know if they are improving at all?

When asked this question, people often respond with the number of books, articles, or tutorial videos they have consumed. However, the truth is that 95% of the information in these sources is irrelevant to them. What's more interesting is that I have seen people, after digesting a ton of information, feeling as if they have not improved at all. Brute-force learning simply does not work; something is wrong.

The German sociologist Niklas Luhmann and contemporary researcher Andy Matuschak proposed the idea that index card writing is the fundamental unit of knowledge work. At face value, one might ask: isn't it just another way of taking notes?

It's not just another way of writing notes; it's much more than that. The process goes as follows:

- Choose a topic or area to study

- Read, have conversations, and reflect on them.

- Write down any provoking thoughts as index cards along with corresponding references. It’s important to avoid copying content and instead use your own words to describe the thoughts

- Regularly review your new index cards against your existing permanent notes.

- During your review session, ask the following questions for each card:

- Does this card complement my existing thoughts? If yes, write a new permanent note.

- Does this card contradict my existing thoughts? If yes, tweak the relevant permanent notes.

- Does this card simply repeat my existing thoughts? If yes, discard it.

- Does this card make any sense at all? If no, discard it.

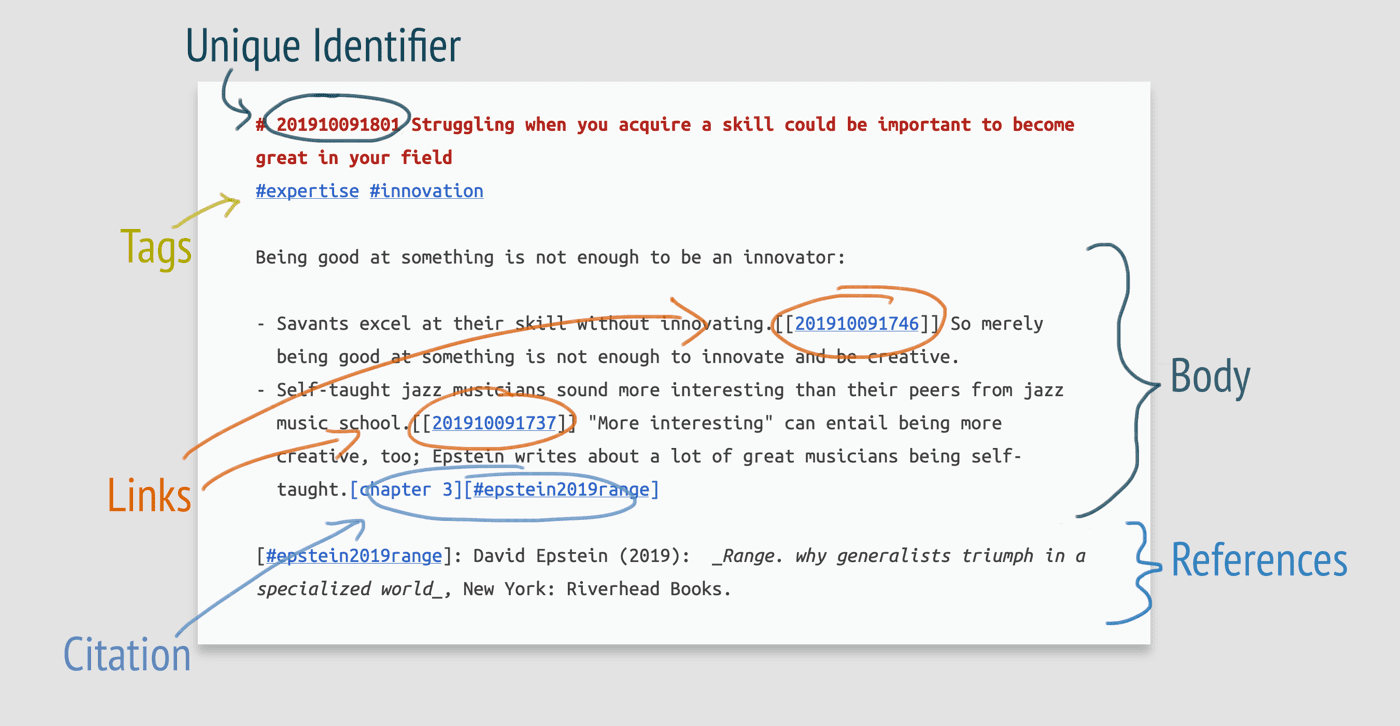

This is an example of what an index card looks like:

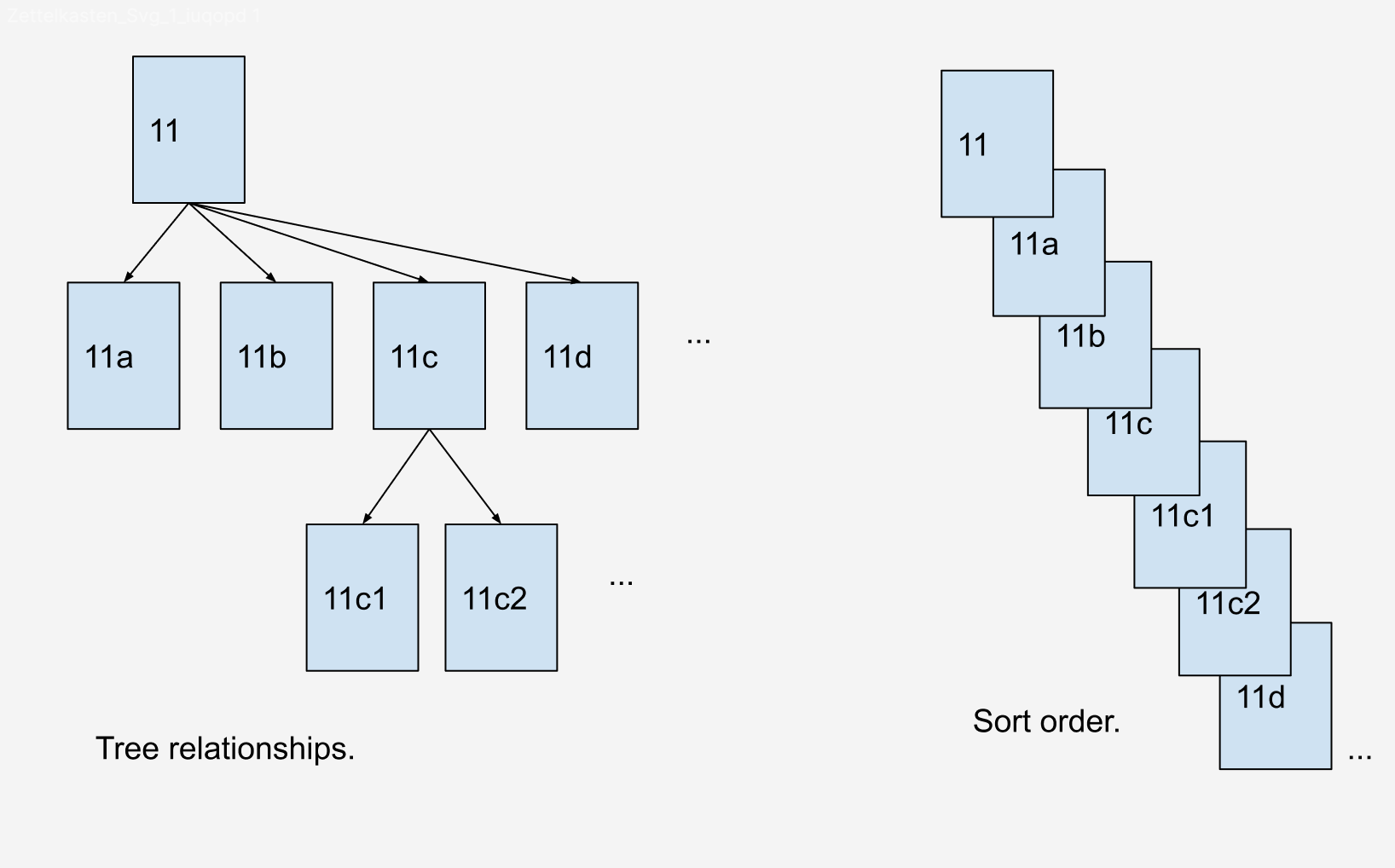

As you continue shaping up the cards, a structure will eventually surface.

If you do it long enough, you might get a visualization of your brain, like the one Tobi Lutke tweeted.

This is what my @logseq graph looks like after a year of daily usage. Don't think I could function without it anymore. pic.twitter.com/LhohV80Puc

— tobi lutke (@tobi) April 20, 2022

Numerous individuals and companies are currently participating in this field, working on various ideas and implementations.

I have been contemplating and monitoring this space for some time now. It appears to be an emerging trend, something that only innovators and early adopters are pursuing. The methodologies and tools currently available are not particularly user-friendly. Nonetheless, I see this as a tremendous opportunity.

Strava for Building Knowledge Graphs

After hearing your talk on the history of the social space and its various issues, I went back and did my own research. It was the Proof for X article by Julian Lehr that really struck me.

In the article, Julian argues that:

When new social networks emerge they have to introduce new proof mechanisms to differentiate themselves from existing incumbents. These can either be novel proof-of-creative-work hurdles or completely new proof-of-x mechanisms.

TikTok is a good example for proof-of-creative-work innovation. The app provides creators with a powerful set of video editing tools that have opened a whole new level of creativity.

Strava, on the other hand, introduced an entirely new proof mechanism: Proof-of-physical-activity. By using your phone’s GPS sensor (or a 3rd-party fitness tracker), users can actually prove how much and fast they ran or cycled. In contrast to Instagram photos, Strava’s proof mechanism is a lot harder to fake (though there are exceptions).

Then it occurred to me, can we standardize index cards and make writing them a proof-of-learning activity? I believe we can.

Then it occurred to me, can we standardize the index card format and make writing a card the proof-of-learning-activity for a social network? I believe we can.

- For those who already write index cards, it is a way to signal their intelligence

- All participants in the network can read high-quality notes and fork them to enhance their own personal knowledge graph

In fact, people are already doing this on Twitter, which is called a Tweetstorm. For example, Andrew Wilkinson tweets about how they lost $10 Million building Flow.

If done correctly, I envision a social network that allows people to share their thoughts on what they're reading or learning as index cards. It's a place where you can accumulate knowledge on various topics, represented in different knowledge graphs.

You can follow people, and the index cards of those you follow will show up in your Card Feed. For each index card, you can fork, comment, or bookmark it depending on how it relates to you:

- If the card augments and fits with your existing knowledge, you can fork a copy and edit it to make it yours, with a reference back to the original card.

- If you have questions, you can leave comments.

- If you find it interesting but aren't sure how it fits into your knowledge graph yet, you can bookmark it.

The counts of forks, comments, and bookmarks will be the quantifiable social capital for everyone who shares their cards, which helps fuel the sharing activity.

The closest model to this is GitHub. The unit of work for GitHub is a commit. You commit to build up projects. Developers, in turn, can fork or star your projects to build their own works on top of yours.

How about AI?

I see many people discussing how the current massive advancement in AI is impacting knowledge workers. I think it's worth discussing AI in the context of what we just talked about.

AI is becoming increasingly good at abstracting common, repeatable knowledge. Here are just a few examples:

- AI for translation, which is vastly cheaper than human translators

- AI for generating fashion model images for brands (such as https://www.deepagency.com)

- In the near future, I believe AI will be able to take a wireframe from a product manager and turn it into a high-fidelity mockup, as well as write the front-end code.

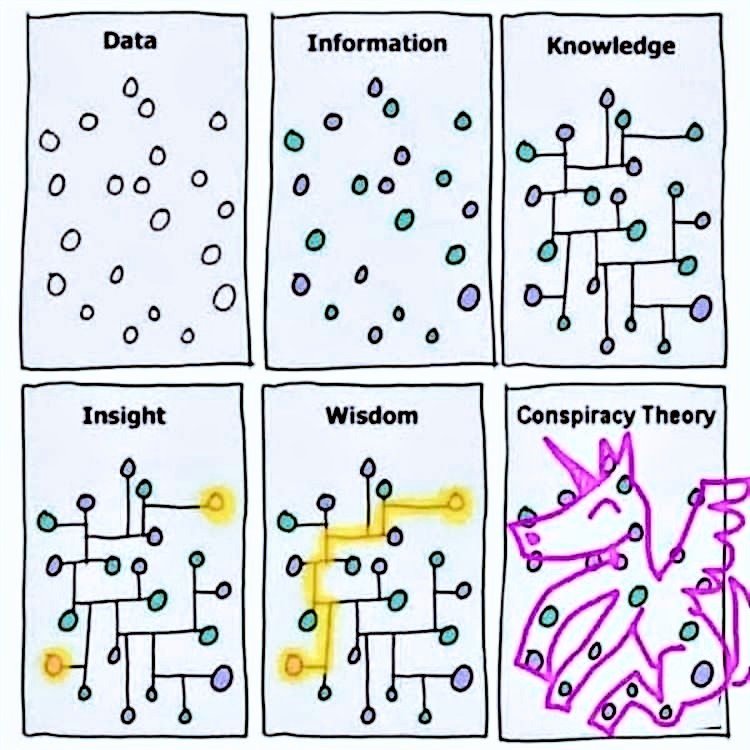

However, having knowledge does not necessarily mean having insight. What we actually look for is insights. To gain insights, you must constantly shape up your knowledge and apply them in practice. AI can make a lot of previously scarce knowledge abundant, enabling insights that were once difficult to obtain to become more accessible. I believe that entrepreneurship will benefit greatly from AI.